The USS Oklahoma Punch Bowl

A history of the USS Oklahoma and Michael Galmer's connection to it

One-Two Punch: Historic Bowl Rests, Replica Serves

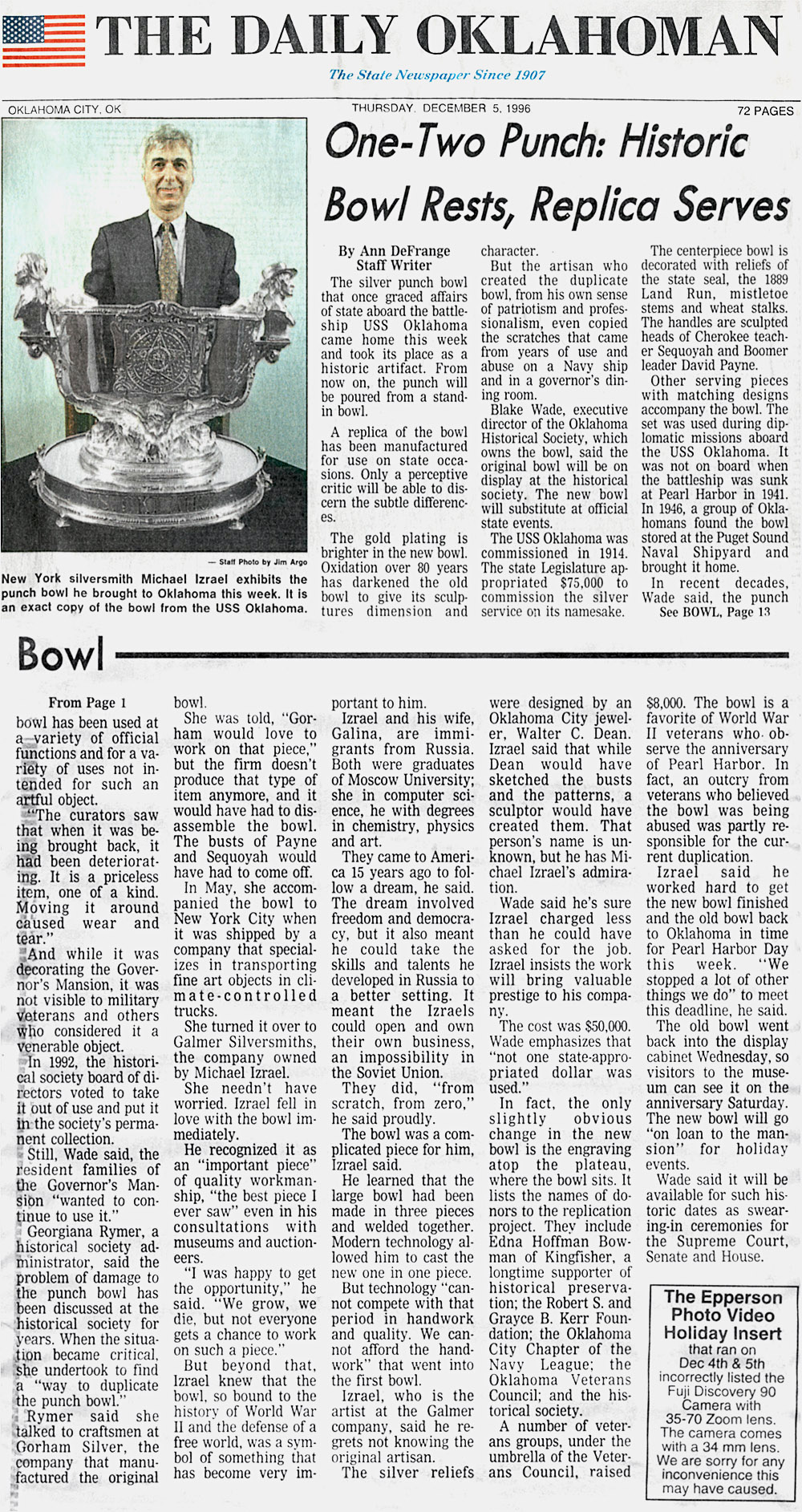

New York silversmith Michael Izrael exhibits the punch bowl he brought to Oklahoma this week. It is an exact copy of the bowl from the USS Oklahoma.

Staff Photo by Jim Argo

The silver punch bowl that once graced affairs of state aboard the battle-ship USS Oklahoma came home this week and took its place as a historic artifact. From now on, the punch will be poured from a stand-in bowl.

A replica of the bowl has been manufactured for use on state occasions. Only a perceptive critic will be able to dis-cern the subtle differences.

The gold plating is brighter in the new bowl. Oxidation over 80 years has darkened the old bowl to give its sculptures dimension and character.

But the artisan who created the duplicate bowl, from his own sense of patriotism and professionalism, even copied the scratches that came from years of use and abuse on a Navy ship and in a governor's dining room.

Blake Wade, executive director of the Oklahoma Historical Society, which owns the bowl, said the original bowl will be on display at the historical society. The new bowl will substitute at official state events.

The USS Oklahoma was commissioned in 1914. The state Legislature appropriated $75,000 to commission the silver service on its namesake.

The centerpiece bowl is decorated with reliefs of the state seal, the 1889 Land Run, mistletoe stems and wheat stalks. The handles are sculpted heads of Cherokee teacher Sequoyah and Boomer leader David Payne.

Other serving pieces with matching designs accompany the bowl. The set was used during diplomatic missions aboard the USS Oklahoma. It was not on board when the battleship was sunk at Pearl Harbor in 1941. In 1946, a group of Oklahomans found the bowl stored at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and brought it home.

In recent decades, Wade said, the punch bowl has been used at a variety of official functions and for a variety of uses not intended for such an artful object.

"The curators saw that when it was being brought back, it had been deteriorating. It is a priceless item, one of a kind. Moving it around caused wear and tear."

And while it was decorating the Governor's Mansion, it was not visible to military veterans and others who considered it a venerable object.

In 1992, the historical society board of directors voted to take it out of use and put it in the society's permanent collection.

Still, Wade said, the resident families of the Governor's Mansion "wanted to continue to use it."

Georgiana Rymer, a historical society administrator, said the problem of damage to the punch bowl has been discussed at the historical society for years. When the situation became critical, they undertook to find a "way to duplicate the punch bowl."

Rymer said she talked to craftsmen at Gorham Silver, the company that manufactured the original bowl.

She was told, “Gorham would love to work on that piece,” but the firm doesn't produce that type of item anymore, and it would have had to disassemble the bowl. The busts of Payne and Sequoyah would have had to come off.

In May, she accompanied the bowl to New York City when it was shipped by a company that specializes in transporting fine art objects in climate-controlled trucks.

She turned it over to Galmer Silversmiths, the company owned by Michael Izrael.

She needn't have worried. Izrael fell in love with the bowl immediately. He recognized it as an "important piece" of quality workmanship, "the best piece I ever saw" even in his consultations with museums and auctioneers.

"I was happy to get the opportunity," he said. "We grow, we die, but not everyone gets a chance to work on such a piece." But beyond that, Izrael knew that the bowl, so bound to the history of World War II and the defense of a free world, was a symbol of something that has become very important to him.

Izrael and his wife, ham Galina, are immigrants from Russia. Both were graduates of Moscow University; she in computer science, he with degrees in chemistry, physics and art.

They came to America 15 years ago to follow a dream, he said. The dream involved freedom and democracy, but it also meant he could take the skills and talents he developed in Russia to a better setting. It meant the Izraels could open and own their own business, an impossibility in the Soviet Union.

They did, "from scratch, from zero," he said proudly.

The bowl was a complicated piece for him, Izrael said.

He learned that the large bowl had been made in three pieces and welded together. Modern technology allowed him to cast the new one in one piece.

But technology "cannot compete with that period in handwork and quality. We cannot afford the handwork" that went into the first bowl.

Izrael, who is the artist at the Galmer company, said he regrets not knowing the original artisan.

The silver reliefs were designed by an Oklahoma City jeweler, Walter C. Dean. Izrael said that while Dean would have sketched the busts and the patterns, a sculptor would have created them. That person's name is unknown, but he has Michael Izrael's admiration.

Wade said he's sure Izrael charged less than he could have asked for the job. Izrael insists the work will bring valuable prestige to his company.

The cost was $50,000. Wade emphasizes that "not one state-appropriated dollar was used."

In fact, the only slightly obvious change in the new bowl is the engraving atop the plateau, where the bowl sits. It lists the names of donors to the replication project. They include Edna Hoffman Bowman of Kingfisher, a longtime supporter of historical preservation; the Robert S. and Grayce B. Kerr Foundation; the Oklahoma City Chapter of the Navy League; the Oklahoma Veterans Council; and the historical society.

A number of veterans groups, under the umbrella of the Veterans Council, raised $8,000. The bowl is a favorite of World War II veterans who observe the anniversary of Pearl Harbor. In fact, an outcry from veterans who believed the bowl was being abused was partly responsible for the current duplication.

Izrael said he worked hard to get the new bowl finished and the old bowl back to Oklahoma in time for Pearl Harbor Day this week. "We stopped a lot of other things we do" to meet this deadline, he said.

The old bowl went back into the display cabinet Wednesday, so visitors to the museum can see it on the anniversary Saturday. The new bowl will go "on loan to the mansion" for holiday events.

Wade said it will be available for such historic dates as swearing-in ceremonies for the Supreme Court, Senate and House.

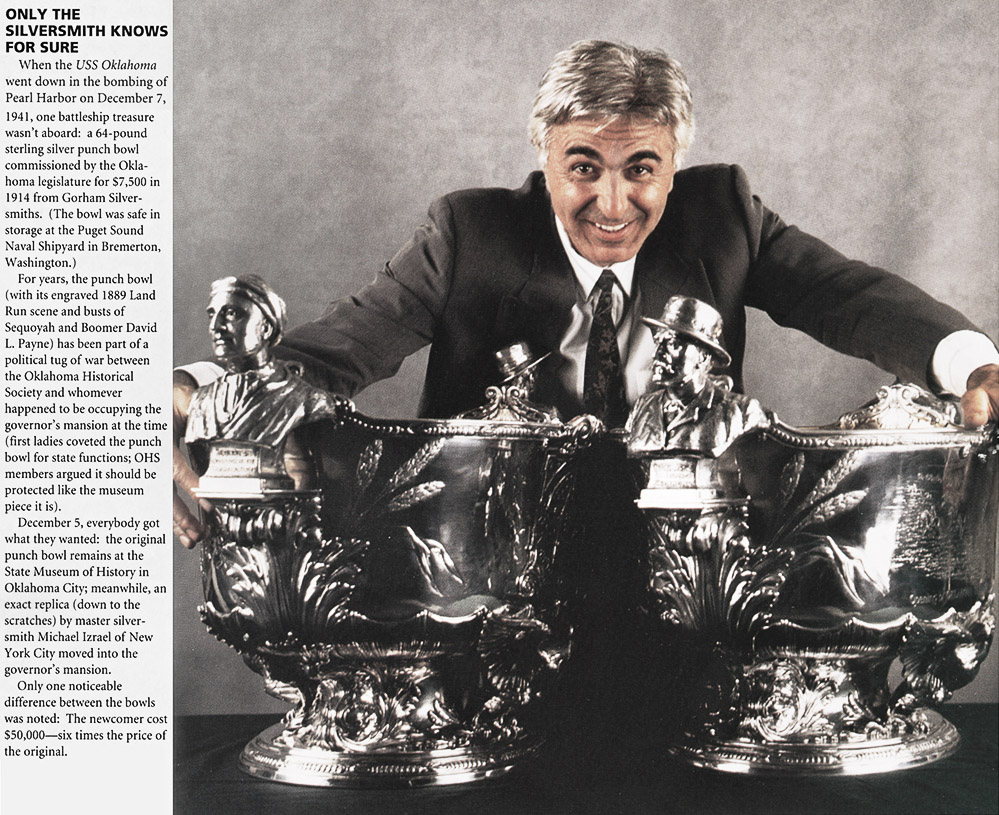

ONLY THE SILVERSMITH KNOWS FOR SURE

When the USS Oklahoma went down in the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, one battleship treasure wasn't aboard: a 64-pound sterling silver punch bowl commissioned by the Oklahoma legislature for $7,500 in 1914 from Gorham Silversmiths. (The bowl was safe in storage at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Washington.)

For years, the punch bowl (with its engraved 1889 Land Run scene and busts of Sequoyah and Boomer David L. Payne) has been part of a political tug of war between the Oklahoma Historical Society and whomever happened to be occupying the governor's mansion at the time (first ladies coveted the punch bowl for state functions; OHS members argued it should be protected like the museum piece it is).

December 5, everybody got what they wanted: the original punch bowl remains at the State Museum of History in Oklahoma City; meanwhile, an exact replica (down to the scratches) by master silversmith Michael Izrael of New York City moved into the governor's mansion.

Only one noticeable difference between the bowls was noted: The newcomer cost $50,000—six times the price of the original.

A Smith Comes To America

Many silver aficionados are surprised to learn that one of America's most prolific, patriotic silversmiths hails from Russia. Reaching these shores with his supportive wife Galina and young daughter Zina in 1981, Michael Izrael Galmer followed a dream of freedom, success, and creative expression—and God bless America, he found it. Opening Galmer Ltd. in a small workshop, his extraordinary talent was swiftly discovered by elite connoisseurs, Tiffany & Co. and, ultimately, museums and historical societies. Michael became known in the industry by his company name and has welcomed opportunities to give back to his adopted country, extending his talent, gratitude, and love for special projects honoring American traditions.

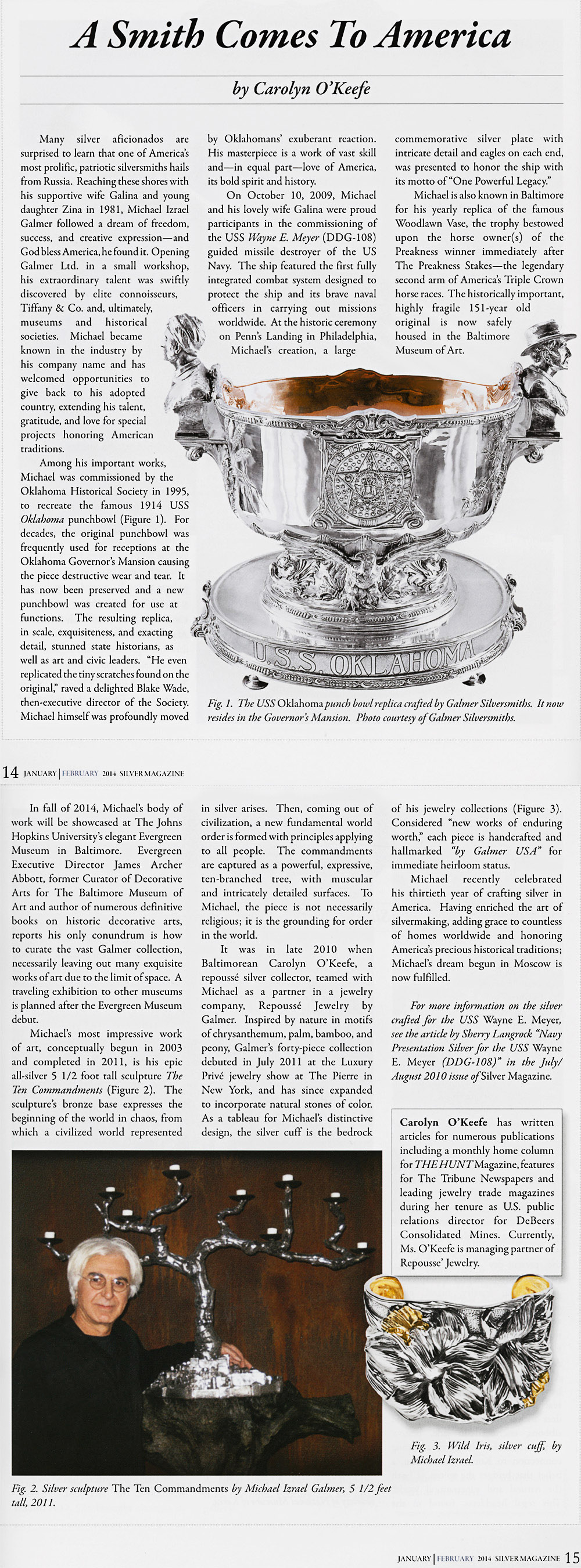

Among his important works, Michael was commissioned by the Oklahoma Historical Society in 1995, to recreate the famous 1914 USS Oklahoma punchbowl (Figure 1). For decades, the original punchbowl was frequently used for receptions at the Oklahoma Governor's Mansion causing the piece destructive wear and tear. It has now been preserved and a new punchbowl was created for use at functions. The resulting replica, in scale, exquisiteness, and exacting detail, stunned state historians, as well as art and civic leaders. "He even replicated the tiny scratches found on the original," raved a delighted Blake Wade, then-executive director of the Society. Michael himself was profoundly moved by Oklahomans' exuberant reaction. His masterpiece is a work of vast skill and—in equal part—love of America, its bold spirit and history.

On October 10, 2009, Michael and his lovely wife Galina were proud participants in the commissioning of the USS Wayne E. Meyer (DDG-108) guided missile destroyer of the US Navy. The ship featured the first fully integrated combat system designed to protect the ship and its brave naval officers in carrying out missions worldwide. At the historic ceremony on Penn's Landing in Philadelphia, Michael's creation, a large commemorative silver plate with intricate detail and eagles on each end, was presented to honor the ship with its motto of "One Powerful Legacy."

Michael is also known in Baltimore for his yearly replica of the famous Woodlawn Vase, the trophy bestowed upon the horse owner(s) of the Preakness winner immediately after The Preakness Stakes—the legendary second arm of America's Triple Crown horse races. The historically important, highly fragile 151-year old original is now safely housed in the Baltimore Museum of Art.

In fall of 2014, Michael's body of work will be showcased at The Johns Hopkins University's elegant Evergreen Museum in Baltimore. Evergreen Executive Director James Archer Abbott, former Curator of Decorative Arts for The Baltimore Museum of Art and author of numerous definitive books on historic decorative arts, reports his only conundrum is how to curate the vast Galmer collection, necessarily leaving out many exquisite works of art due to the limit of space. A traveling exhibition to other museums is planned after the Evergreen Museum debut.

Michael’s most impressive work of art, conceptually begun in 2003 and completed in 2011, is his epic all-silver 5 1/2 foot tall sculpture The Ten Commandments (Figure 2). The sculpture's bronze base expresses the beginning of the world in chaos, from which a civilized world represented in silver arises. Then, coming out of civilization, a new fundamental world order is formed with principles applying to all people. The commandments are captured as a powerful, expressive, ten-branched tree, with muscular and intricately detailed surfaces. To Michael, the piece is not necessarily religious; it is the grounding for order in the world.

It was in late 2010 when Baltimorean Carolyn O'Keefe, a repoussé silver collector, teamed with Michael as a partner in a jewelry company, Repoussé Jewelry by Galmer. Inspired by nature in motifs of chrysanthemum, palm, bamboo, and peony, Galmer's forty-piece collection debuted in July 2011 at the Luxury Prive jewelry show at The Pierre in New York, and has since expanded to incorporate natural stones of color. As a tableau for Michael's distinctive design, the silver cuff is the bedrock of his jewelry collections (Figure 3). Considered "new works of enduring worth," each piece is handcrafted and hallmarked "by Galmer USA" for immediate heirloom status.

Michael recently celebrated his thirtieth year of crafting silver in America. Having enriched the art of silvermaking, adding grace to countless of homes worldwide and honoring America's precious historical traditions; Michael's dream begun in Moscow is now fulfilled.