The Preakness Trophy

A history of the Woodlawn Vase Preakness Trophy and Michael Galmer's connection to it

The Take-home Woodlawn Vase

No one gets to take the Woodlawn Vase home anymore.

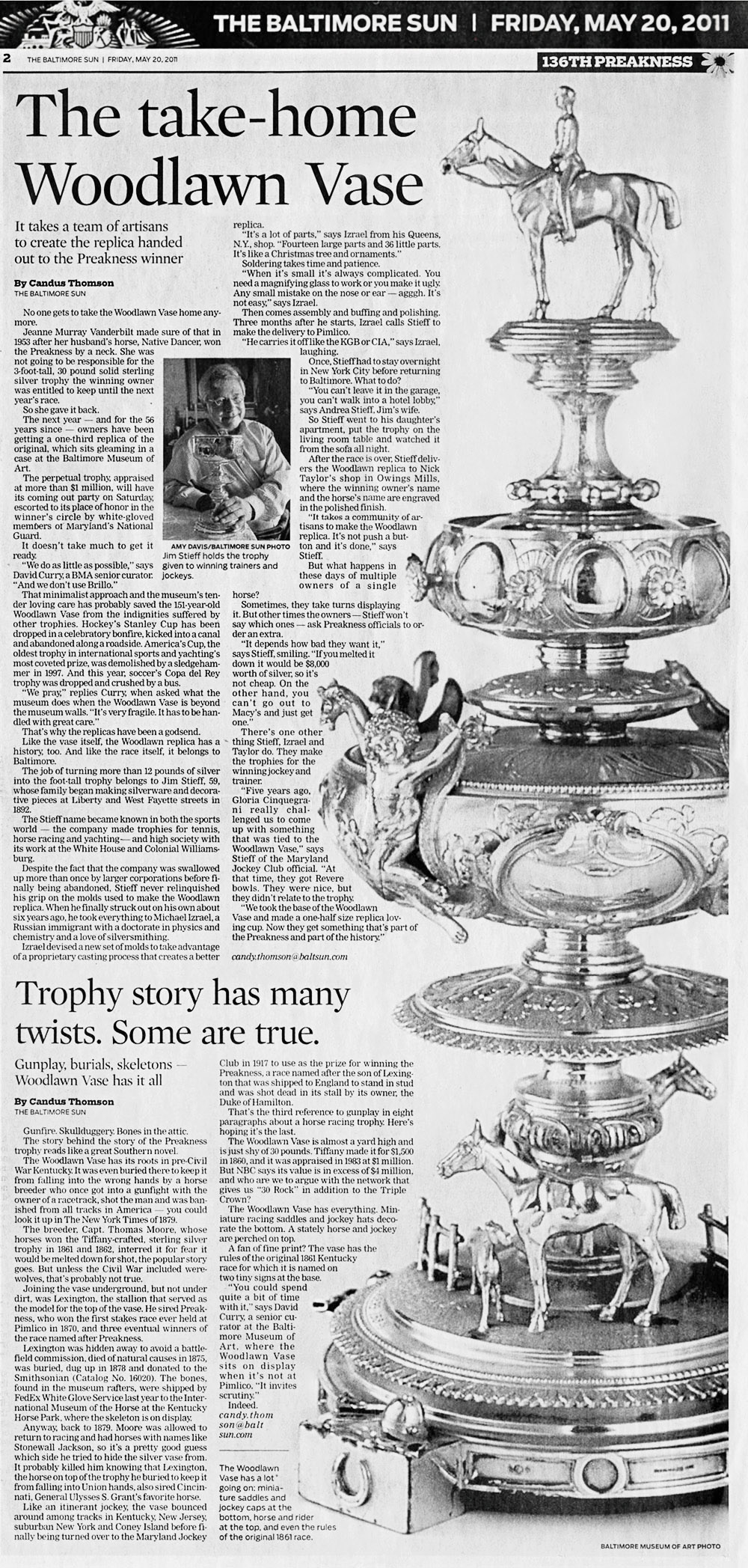

Jeanne Murray Vanderbilt made sure of that in 1953 after her husband’s horse, Native Dancer, won the Preakness by a neck. She was not going to be responsible for the 3-foot-tall, 30 pound solid sterling silver trophy the winning owner was entitled to keep until the next year’s race.

So she gave it back.

The next year - and for the 56 years since - owners have been getting a one-third replica of the original, which sits gleaming in a case at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

The perpetual trophy, appraised at more than $1 million, will have its coming out party on Saturday, escorted to its place of honor in the winner’s circle by white-gloved members of Maryland’s National Guard.

It doesn’t take much to get it ready.

“We do as little as possible,” says David Curry, a BMA senior curator. “And we don’t use Brillo.”

That minimalist approach to the museum’s tender loving care has probably saved the 151-year-old Woodlawn Vase from the indignities differed by other trophies. Hockey’s Stanley Cup has been dropped in a celebratory bonfire, kicked into a canal and abandoned along a roadside. America’s Cup, the oldest trophy in international sports and yachting’s most coveted prize, was demolished by a sledgehammer in 1997. And this year, soccer’s Copa del Rey trophy was dropped and crushed by a bus.

“We pray,” replies Curry, when asked what the museum does when the Woodlawn Vase in beyond the museum walls. “It’s very fragile. It has to be handled with great care.”

That’s why the replicas have been a godsend.

Like the vase itself, the Woodlawn replica has a history, too. And like the race itself, it belongs to Baltimore.

The job of turning more than 12 pounds of silver into the foot-tall trophy belongs to Jim Stieff, 59, whose family began making silverware and decorative pieces at Liberty and West Fayette streets in 1892.

The Stieff name became known in both the sports world - the company made trophies for tennis, horse racing and yachting - and high society with its work at the White House and Colonial Williamsburg.

Despite the fact that the company was swallowed up more than once by larger corporations before finally being abandoned, Stieff never relinquished his grip on the molds used to make the Woodlawn replica. When he finally struck out on his own about six years ago, he took everything to Michael Izrael, a Russian immigrant with a doctorate in physics and chemistry and a love of silversmithing.

Izrael devised a new set of molds to take advantage of a proprietary casting process that creates a better replica.

“It’s a lot of parts,” says Izrael from his Queens, N.Y., shop. “Fourteen large parts and 36 little parts. It’s like a Christmas tree and ornaments.”

Soldering takes time and patience.

“When it’s small it’s always complicated. You need a magnifying glass to work or you make it ugly. Any small mistake on the nose or ear - agggh. It’s not easy,” says Izrael.

Then comes assembly and buffing and polishing. Three months after he starts, Izrael calls Stieff to make the delivery to Pimlico.

“He carries it off like the KGB or CIA,” says Izrael, laughing.

Once, Stieff had to stay overnight in New York City before returning to Baltimore. What to do?

“You can’t leave it in the garage, you can’t walk into a hotel lobby,” says Andrea Stieff, Jim’s wife.

So Stieff went to his daughter’s apartment, put the trophy on the living room table and watched it from the sofa all night.

After the race is over, Stieff delivers the Woodlawn replica to Nick Taylor’s shop in Owings Mills, where the winning owner’s name and the horses name are engraved in the polished finish.

“It takes a community of artisans to make the Woodlawn replica. It’s not push a button and it’s done,” says Stieff.

But what happens in these days of multiple owners of a single horse?

Sometimes, they take turns displaying it. But other times the owners - Stieff won’t say which ones - ask Preakness officials to order an extra.

“It depends how bad they want it,” says Stieff, smiling. “If you melted it down it would be $8,000 worth of silver, so it’s not cheap. On the other hand, you can’t go out to Macy’s and just get one.”

There’s one other thing Stieff, Izrael and Taylor do. They make the trophies for the winning jockey and trainer.

“Five years ago, Gloria Cinquegrani really challenged us to come up with something that was tied to the Woodlawn Vase,” says Stieff of the Maryland Jockey Club official. “At that time, they got Revere bowls. They were nice, but they didn’t relate to the trophy.

“We took the base of the Woodlawn Vase and made a one-half size replica loving cup. Now they get something that’s part of the Preakness and part of the history.”